Once Upon a Time

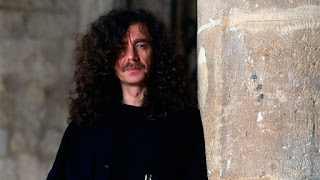

James Dillon

When the premiere of a work called ‘Once Upon a Time’ at the

Huddersfield Festival of 1980, James Dillon was immediately thrust

centre stage. Hitherto, James Dillon's

success had been variable. Mainly

learning his craft in libraries rather than formal institutions and without the

prospect of a performance at the end, many of his early pieces were left

incomplete. The first substantial work Babble

(1974-6) was a brief glimpse of things to come.

Although now James Dillon disregards the rigorous architectural design

in which everything 'is mapped out despite the material'. After the first section was rehearsed by the

newly formed Charles Ives Choir who were perplexed by some of the graphic

notation, the work was abandoned. His

momentary interest in serialism in ‘Dillug-Kefitsah’ (1976) encouraged James

Dillon to examine the seemingly paradoxical notion of a 'parametrical

discipline' working against an ‘experimental freedom’. As a result, he had cultivated such a real

sense of artistry that he was enabled to publicly document his 'first

work'. Finally, he had begun to

unshackle himself from the problems of infrastructure which had dogged his

earlier works (a difficulty which is perhaps more evident for a largely

self-taught composer). However, this

work was not yet a solution to the kind of schism between ‘process’ and ‘form’

that he had encountered in the earlier work ‘Babble’. What was needed was a completed re-evaluation

of the process of composition. Around

this time, Xenakis produced his inspired thoughts on the essential aspects of

composition in a book called Formalised Music.

Now, James Dillon was encouraged to reject the notion of heterophony

(counterpoint, melody, harmony) and serialism that was very much a concern of

his contemporaries for an amorphous texture generated by generalised

principles. Perhaps unconsciously,

James Dillon was about to create his own individual style as characterised in ‘Once

Upon a Time’. However, and this is

perhaps what makes James Dillon such an interesting figure, such a

straightforward analysis of his early work as a composer is somewhat naïve, especially

when the two previous works written around the same time are taken into

consideration. The solo clarinet work ‘Crossing

Over’(1978) uses material from a wide range of sources and so does the solo

drum work that followed, ‘Ti.re-Ti.ke-Dha’(1979). The title of the latter work is derived from

the verbal instructions given to drummers of North Indian Classical Music (‘Dha’

indicates both hands in the centre; ‘Ti’ is a kind of 'rim-shot' etc...). Combinations of words indicate a ‘Tal’ or a

repetitive rhythmic pattern and the title of the James Dillon piece appears to

be a fragment of one just like the third and fourth beats of the Ektål:

1 2 3 4

Dhin Dhin Dhage Ti.ra.ki.ta

etc...

In this respect, James Dillon’s music represents an apparent

contradiction; rigorous in terms of application but derived from a diverse inspiration. This indicates a powerfully creative but strongly independent mind.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Dillon_(composer)

http://www.fonemaconsort.com/blog-archives/#james-dillon

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Dillon_(composer)

http://www.fonemaconsort.com/blog-archives/#james-dillon